This post is part of a series.

- Part 1: This Post

- Part 2: Feature Switch Rule Definitions

Intro

In any sufficiently large system (and honestly, plenty of smaller ones), it can be useful to be able to turn features on and off, ramp up new features slowly, or disable features for specific devices or users. To do this, most systems use feature switches (also known as feature flags or feature toggles).

This is the first in a series of posts where we’ll build a feature switch rules engine.

What is a feature switch?

Let’s start by defining what we mean when we say feature switch. We’ll define it as a key-value pair where the key represents a feature name (as a string) and the value represents the current state of a feature (e.g. a boolean, number, string, Array<primitive>, etc.). You can imagine a feature like backgroundColor being set to "blue" or enableAlgorithmV3 being set to true.

Feature switches can be broken down into a few different categories:

- Operational switches - these are used to enable or disable features in production. You might use them to disable features that are not yet ready for production, or to turn off a feature that is causing problems in production. These switches typically are either on or off, but you might want to support percentage-based rollouts or shutdowns to verify behavior or to reduce load.

- Experiment switches - these are used to enable or disable features for a subset of users. They are typically used to test new features with a small percentage of users before rolling them out to everyone. These could be used in an A/B testing system where metrics are collected based on which treatment a user experiences.

- Context-aware switches - these are used to enable or disable features for specific environments (eg, prod/staging/dev), users (eg, employees/beta testers/public users), or devices (eg, iPhone/Android/Web devices).

This switch classification is not mutually exclusive. For example, both your operational switches and experiment switches would likely benefit from being context-aware. By doing so, you could disable a broken feature for a specific version of a device or enable an experiment in a single country.

The rules engine we will be building will be able to handle all of these types of feature switches, with the caveat that experimentation adds some additional complexities that we will not be covering in this series.

A typical feature switch API

A typical feature switch API might look something like this:

1const featureSwitches = buildFeatureSwitches();

2const userContext = { userId: 123, countryCode: 'CA', os: 'iOS' };

3const isAlgorithmV3Enabled =

4 featureSwitches.getValue<boolean>(userContext, 'enableAlgorithmV3');

There’s a lot of hand-waviness going on behind the scenes inside buildFeatureSwitches(), which depends entirely on the implementation of the feature switch rules engine. But the important thing is that we can pass in a user context and a feature name and get back a value.

Short and Simple

A basic rules engine could be implemented as a set of Matchers for each rule. In this basic engine, you might have a Matcher that matches on UserIds, or a Matcher for country codes, and perhaps a way to combine matchers into more complex rules (eg, And / Or matchers that are composed of other underlying matchers).

1class UserIdMatcher implements Matcher {

2 constructor(private userId: number) {}

3

4 matches(userContext: Context): boolean {

5 return userContext.userId === this.userId;

6 }

7}

8

9const allFeatureSwitchRules = [

10 // sets "enableAlgorithmV3" to true for user 123

11 new FeatureSwitchRule('enableAlgorithmV3', true, new UserIdMatcher(123)),

12 // sets "logo" to "my-logo-ios.png" for iOS devices

13 new FeatureSwitchRule('logo', 'my-logo-ios.png', new OSMatcher('iOS')),

14 // enable new home page for 50% of canadian users

15 new FeatureSwitchRule('enableNewHomePage', true,

16 new And([new CountryCodeMatcher('CA'), new RandomUserSelector(0.5)])),

17];

18

19// define the possible types of feature switch values

20type FeatureSwitchValue = string | boolean | number | Array<FeatureSwitchValue>;

21

22// this class represents all of the feature switches for a given user context

23class UserFeatureSwitches {

24 private readonly featureSwitchValues: Map<string, FeatureSwitchValue>;

25

26 constructor(userContext: Context, private rules: FeatureSwitchRule[]) {

27 this.featureSwitchValues = new Map();

28

29 for (rule of allFeatureSwitchRules) {

30 if (rule.matches(userContext)) {

31 // if the rule matches, set the value defined in the rule

32 // note: if two rules match, the last one wins

33 this.featureSwitchValues.set(rule.featureName, rule.value);

34 }

35 }

36 }

37

38 getValue<T extends FeatureSwitchValue>(featureName: string): T | undefined {

39 return this.featureSwitchValues.get(featureName) as T | undefined;

40 }

41}

This is nice and simple, and for a lot of applications it’s probably all you need. But in a more complex system where you might be dealing with hundreds or thousands of feature switches, each with their own complex and overlapping rules, this approach can quickly become unwieldy.

The problem is that each rule more-or-less amounts to one or more if statements, along with potentially expensive transformations like generating hashes. And if there are rules with the same matchers, they get evaluated each time. While these operations may not have a large toll for a single rule, they can quickly add up when you have hundreds or thousands of rules.

Generally speaking, we want feature switches to be blazingly fast. Our UI may need to delay rendering until results are evaluated, so we want to be able to evaluate them as quickly as possible. And if we’re using feature switches to gate expensive operations, we want to be able to evaluate them as quickly as possible to avoid wasting resources.

If our goal is a more scalable system (and for the sake of this series, it is!), we need to find a better way.

Re-structuring Our Approach

Let’s take a step back.

We can imagine each of our feature switch rules as a query that we want to run against a user context. For example, consider a rule like this:

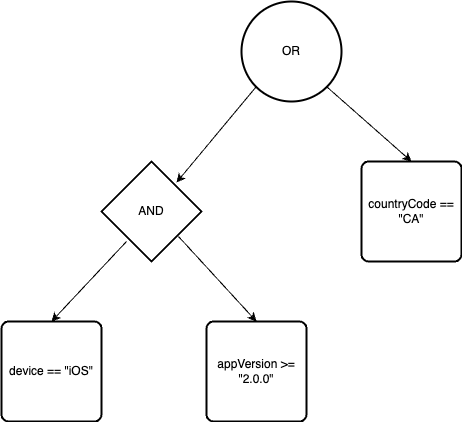

1(deviceOS == "iOS" AND appVersion >= "2.0.0") OR countryCode == "CA"

Breaking down the query:

- We have three criteria (

deviceOS,appVersion, andcountryCode) - Each criteria has an operator (

==or>=) - Each criteria has a value it is being compared against (

"iOS","2.0.0", and"CA") - Additionally, the query is composed together using

AND,OR, and parentheses

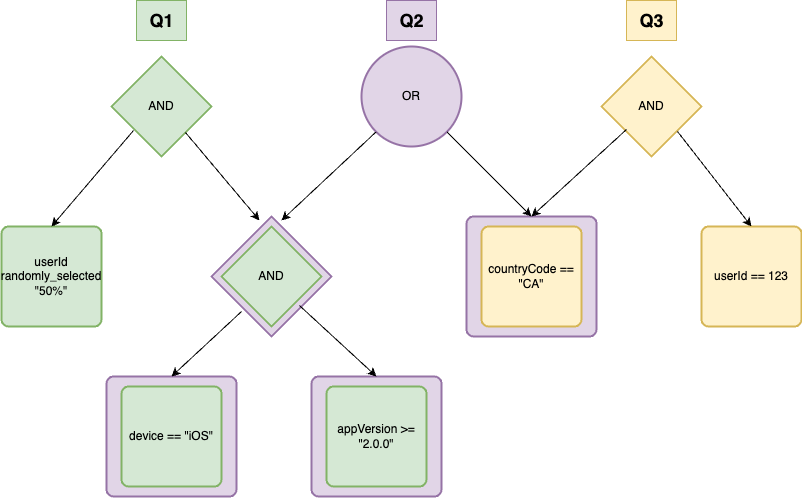

We can also think of this query as being composed of subqueries. Each AND, OR, and parentheses help define how these subqueries combine together. We can represent this query as a tree:

As more and more rules are added, we can imagine that there will be a lot of overlap between the criteria. Let’s add a few more queries to our tree.

1Q1: (deviceOS == "iOS" AND appVersion >= "2.0.0") AND userId randomly_selected "50%"

2Q2: (deviceOS == "iOS" AND appVersion >= "2.0.0") OR countryCode == "CA"

3Q3: countryCode == "CA" AND userId == 123

We can visualize all three queries combined into a single tree, with matching subqueries combined together.

Notice the overlapping subqueries (represented by nodes with two colors). By structuring our queries in this way, we’ve already taken the first step toward optimizing them! When we de-duplicate our subqueries, we are able to evaluate that entire portion of the tree a single time and then reuse the result.

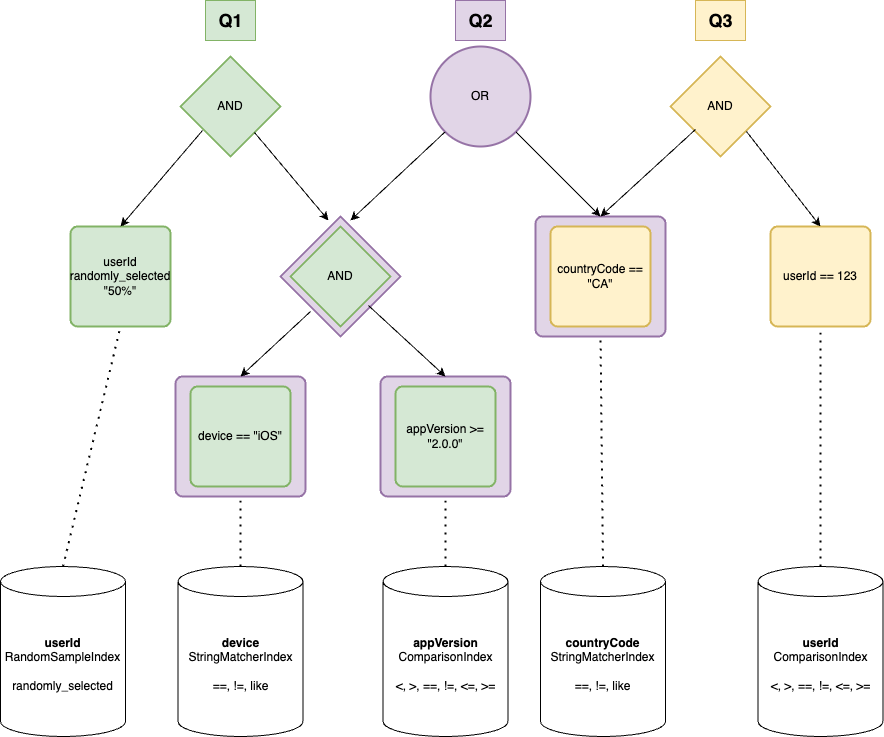

Operators and Indexes

You may have noticed that I slipped in a new operator in the last example: randomly_selected. This is fairly straightforward on the surface; it should return true for 50% of userIds. But it introduces a new wrinkle. We can’t just compare the value of userId to "50%". So, how do we evaluate this operator? And just as importantly, what is responsible for evaluating it?

The short answer is: an index! An index is a data structure that allows us to quickly look up values. An index can be tailor-made to optimize various lookups, such as equality checks, range checks, or even more complex operations like our randomly_selected operator.

Each index is limited to a single criteria, but it may be able to provide multiple operators for that criteria. For example, we might have an index for deviceOS that provides == , !=, and LIKE operators, and another index for appVersion that provides comparison operators (<, >, ==, <=, >=). Each index will use the most appropriate underlying data structure for doing fast lookups of their provided operators.

So there is an implicit relationship between the nodes in our graph, and the index that can evaluate them.

Notice that there are multiple indexes for userId. This is because we have multiple operators for userId. We can’t use the same index for == and randomly_selected, because they require different underlying data structures. We’ll talk more about this in a future post.

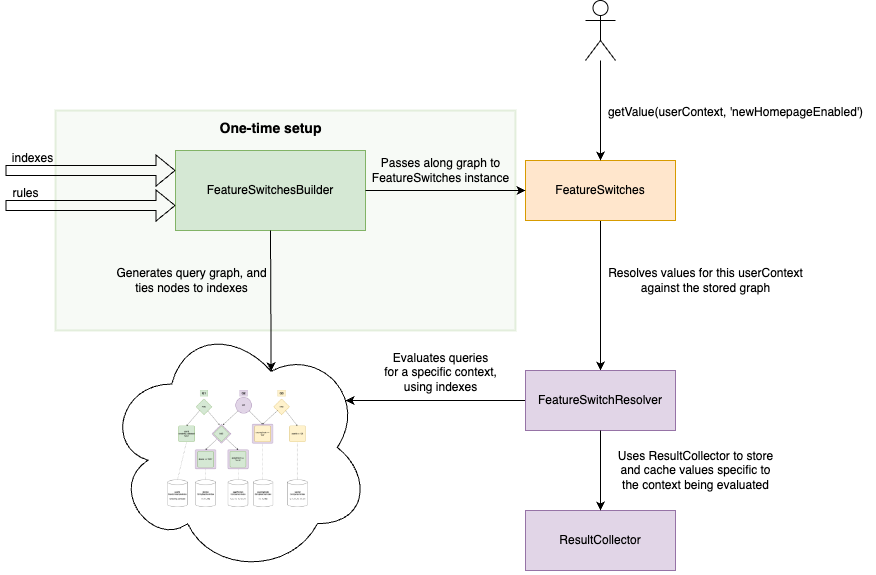

Putting the Pieces Together

So, we know that we want to represent our rules as a tree of queries, and we have indexes that can evaluate each node in the tree. But how does this all fit into the bigger picture?

As you can imagine, there’s a lot of detail that is missing from this diagram. The next posts in the series will each focus on a different component of this architecture. By the end of the series, we will have a fully functional feature switch system that can easily scale to thousands of rules.